|

Nell Gwyn, the Drury Lane girl

'Pray, good people, be civil. I am the Protestant whore'

The great mistresses of the past have made as much, if not more, history than the queens. At a time when love marriages for members of royal families were virtually unthinkable, it was the fascinating female figures who were able to win the affections of a ruler and wield power and influence.

Names such as Madame de Pompadour and Madame de Maintenon, who flourished at the French court, are often better known than the wives of the kings at whose courts they made their careers.

The word maîtresse means 'mistress', and that is what they were, clever and beautiful women who often held court more grandly than the queens. Anyone who aspired to such a career had to be as clever as they were tough – for although the king's favourite held a very high position, she could also fall very low. Take Barbara Villiers, the legendary Countess of Castlemaine, the longtime mistress of Charles II, King of England, known as much for her capriciousness as her extravagance.

Most 'official' mistresses came from the lower nobility, but this could change very quickly if they managed to maintain their position. A clever woman would become much richer and be dismissed from the King's favour with a higher title, especially if she had children by him. Charles II, nicknamed 'The Merry Monarch' by his subjects because of his profligate love life, was usually faithful to his mistresses for years if he was the father of their children. His mistresses have a firm place in history and can still be admired today in a series of paintings by contemporary painter Sir Peter Lely.

One of these women was extremely popular with the public – probably because the actress Nell Gwyn (1650-1687) came from a very humble background. She had a difficult family life, growing up without a father and having to look after her mother and sister from an early age. Nell Gwyn was probably a street girl, a child prostitute as we would call it today. In those days, a girl of fifteen was considered an adult, and childhood was as short as the prime of life for women of the lower classes. Nell came from Drury Lane, which was outside London, surrounded by fields and meadows. But the street was a kind of red-light district, with one brothel after another.

Nell came to the theatre, first as an 'orange girl' selling fruit and sweets to the audience, then as an actress. She had a natural talent, was quick-witted and had a sense of humour. Unable to read, she learned her roles by having the lines read to her. Nell Gwyn's fresh and unspoilt manner soon won her many admirers, increasingly from the aristocracy. A poor girl who was pretty and clever hoped to find a rich gentleman at the theatre who would keep her. There was no other chance of a better life for women like Nell Gwyn. But when the young actress was introduced to the king, an extraordinary destiny took its course. Charles II of England loved women above all else, and he was enchanted by Nell.

Unlike her rivals, the former prostitute asked for very little – a position at court meant nothing to her. Nell must have been a warm and intelligent woman, for she saved Charles from many embarrassments. His mistresses sometimes forgot that their position was not rock-solid, but rather unstable, and Louise de Kérouaille's hysterical fits kept the royal court on its toes and caused gossip beyond the borders of the country. The people loved Nell Gwyn for her simplicity and for not pretending to be more than she was. Her quips are still legendary – once her carriage was pelted with rubbish because it was mistaken for that of the Catholic Madame de Kérouaille. Mrs Gwyn stuck her head out of the couch and said: 'Pray, good people, be civil. I am the Protestant whore.'

Nell Gwyn had several children by King Charles II, for whom she begged for various things. She never interfered with the King's business or his love affairs. This wisdom earned her a good position for many years and the deep friendship of Charles II after their relationship gradually changed. It is possible that the Drury Lane girl loved the king for who he was – not for his position. This would have been in keeping with Nell's character, for she never abused her position to wield power, as others of her 'class' did.

When Charles II died, she was denied access to him and permission to mourn him. Nell died before the age of forty, and for her funeral she demanded all the pomp and splendour she had avoided in life – the funeral cost nearly four hundred pounds, an enormous sum in those days. An anecdote from her life illustrates what little Nell of Drury Lane stood for: when her coachman once tried to beat up a man who had called her a whore, Nell Gwyn stopped him with these words: 'Well, actually, that's a fair remark.' No wonder she was loved.

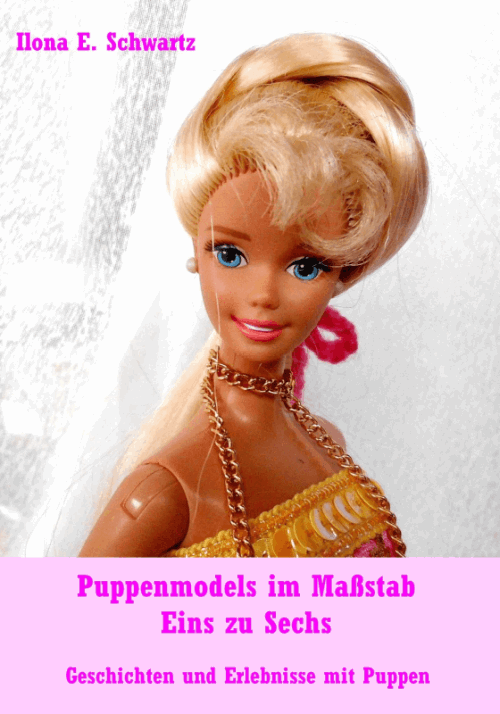

© 'Nell Gwyn, the Drury Lane girl': An article by Pressenet (translated by Izabel Comati), 05/2025. Image shows a painting of Nell Gwyn by Sir Peter Lely, circa 1680, licence: public domain.

– Transgender identity: The journey from Hendrik to Emilia

– Swinging a pendulum. Communicate with your inner self

– Using Tarot cards for decision-making

Discover more articles! Use the search function:

English archive:

More reviews, book presentations and essays

2024/2025

German archive:

2024 |

2023 |

2022 |

2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

2018 |

2017 |

2016 |

2015 |

2014 |

2013 |

2012 |

2011 |

2010 |

2009

Become a writer for Pressenet! Write articles for our online magazine on trending topics such as best books to read, health and wellness, technology and gadgets, business and finance, travel and tourism, lifestyle and fashion or education and career. Info: Become an author

Sponsors and investors are welcome: If you found our articles interesting, we would be grateful for a donation. Please also recommend us to your networks. Thank you very much!

Sitemap About Privacy Policy RSS Feed